The Mzansi Game Jam

This article is the first of three parts in a broader research of practical applications of game studies’ findings in the Netherlands. You can find the second about Discursive Game Design here (COMING SOON!), and the third about Design of Social Interactions here (COMING SOON!).

How do you simulate a climate crisis? How can you convey an ecocritical message that invites reflection and, perhaps, action? In a month’s time, participants of the Mzansi Game Jam (MGJ) developed games that addressed these questions from various angles. This article approaches game jams, with the MGJ as case study, as one of the ways in which game studies scholars may apply the findings of their research in a practical setting. The MGJ, within this context, becomes a platform where participants can acquire a toolset for creating games that challenge dominant perspectives on climate justice. After a literature review on the defining characteristics of a game jam, I identify the MGJ as a type of “radical jamming”: a notion coined by game scholar and creator Sabine Harrer to describe game jams where the organisers use ideological constraints to encourage game design processes that “challenge the default.”1 The radical design principles that can be recognised in the MGJ highlight how game studies scholars can apply their findings to challenge dominant narratives. To learn more about the organisers’ goals and their experience of the event an interview was held in an informal setting.

We’ve worked a lot with game design and co-creative practices. […] We call it a game jam but we really wanted to approach it a bit more from this co-creative side.”

Adriaan Odendaal2

The Internet Teapot Studio is a collaboration led by researchers and designers Karla Zavala Barreda and Adriaan Odendaal. Inspired by the 1998 absurd Hyper Text Coffee Pot Control Protocol (HTCPCP), the studio seeks to reshape the digital to be “more human, more conscientious, and more sustainable.”3 By foregrounding the intertwinement of digital technology and culture, Internet Teapot shows a humanistic approach towards the digital technological. Previous workshops hosted by Internet Teapot focused on the co-creation of an e-zine during which participants engaged critically with algorithms. Their goal was to foster critical algorithmic literacy and help better understand how algorithmic systems impact our lives.4

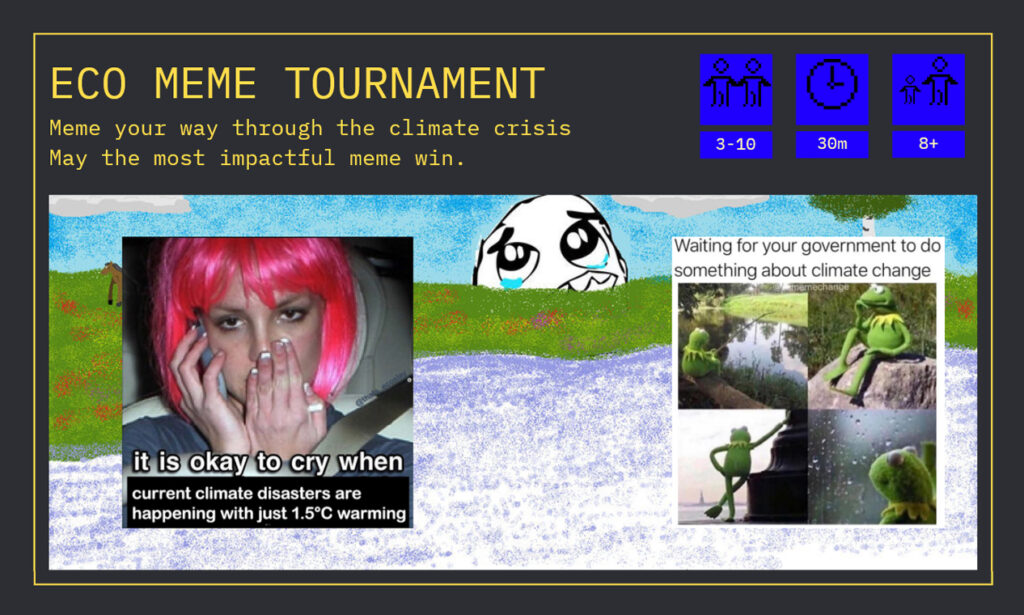

The Mzansi Game Jam (MGJ) consisted of 2 groups of 12 “change-makers” (designers, developers, activists, artists, musicians, writers, makers, and dreamers) from the Netherlands and South Africa. These groups have collaborated during several game jam sessions in June 2025 to create games with an ecocritical message that challenges dominant narratives. Each session was accommodated with an opening talk or community talk to inspire the creatives. Dr. Mmatshilo Motsei, Pf. Dick Ng’ambi, and environmental scientist Mulako Kabisa focused on how (South) African culture may inspire ecological and sustainable thinking, with examples of creation stories, indigenous games, and African-informed transformative change. Additionally, Pf. Stefan Werning, Dr. Laura op de Beke, and Molleindustria (Paolo Pedercini) presented on games’ capabilities for change, how subversion may create impactful moments during gameplay, and the context of making games during political crisis.

Both the participants and organisers generally experienced the MGJ as positive and successful, as can be seen in the jam reports and the podcast Creating in Colour.5 Participants also shared their positive experiences with me at the 2025 Dutch DiGRA symposium. Odendaal reflects on this success:

We had like really good feedback from people […] from […] game design space that said like they never thought about using games in this sense, […] we had some climate researchers and activists and they were like ‘oh this is actually like a really new way of thinking, how to communicate, how to connect with people.'”6

Barreda and Odendaal highlight throughout the interview that it was their aim not to educate the participants from a top-down perspective, but to give them the tools and platform to create their own stories.7 They both used the game jam as a format and deviated from it as a means to share insights from game scholars and climate activists, as is illustrated by Barreda:

What we wanted to do is mostly challenge this idea of competition and see if whether it [a game jam] is a platform to create a community and a platform as well to learn.”8

To see how the MGJ adhered to or deviated from other game jams, it is important to define what makes a game jam. This proves to be a difficult task: there is a plethora of game jams, which complicates the unification of the practice under a single definition.

What is a Game Jam?

Annakaisa Kultima, a Finnish game studies scholar who has both organised and attended more than 50 game jams, formulates a tentative definition after analysing research on game jams between 2006 and 2014:

A game jam is an accelerated opportunistic game creation event where a game is created in a relatively short timeframe exploring given design constraint(s) and end results are shared publically.

Annakaisa Kultima.9

This definition is left broad on purpose: there are many different ways in which a game jam may take shape. With the wide variety of game jams, a precise definition necessarily excludes events that vary in form. For example, the timeframe of the MGJ, compared to other game jams, is relatively long – several sessions over the course of a month, instead of a 24-72 hour marathon. Were the definition of a game jam more specific, it might not cover the MGJ. A precise definition is especially problematic for game jams that have opposing qualities: while the Global Game Jam highlights that it is not a competition, other game jams, like the Imaginary Game Jam, give out prizes to its winners, who are decided via judges.10 Despite their differences, game jams are generally positively experienced, and carry educational value for game design and participatory development.11

Game jams are not only different in form, they also invoke many different forms of activity. Kultima writes that game jams have been approached in academic research from a wide variety of frames, which is unsurprising given the rich context of these events.12 For the MGJ, one of its primary aims is to “…make games that present new perspectives on climate justice and reimagine our climate futures.”13 The MGJ is therefore not competitive in nature, rather, it is activist and seeks to build community.

When people are thinking of game design then they share at least one level of language. […] What we wanted […] was to give them the tools so that they can all speak at least the same language. Because most of the things with intercultural communication comes from not understanding whether a word or something means the same in another context.”

Karla Zavala Barreda.14

Games as a medium facilitate the diffusion of eco-awareness. According to literature and games scholar Péter Kristóf Makai “…games are particularly suited to model the climate crisis”. Climate change is a problem consistent of multiple, often interrelated, factors. Drawing on research by Koenitz, Backe, Bogost, and Murray, Makai argues that games can help players parse these natural and sociocultural factors in several ways: games connect human actions to rule-based systems, they highlight cause-and-effect relationships via game mechanics, and they reduce complexities to a manageable level to allow the player to have a sense of the repercussions of their actions. In other words, games render the complex climate problem comprehensible, and give the player an idea of their agency in combating climate change. Makai concludes, however, that agency in games is often supercharged, which highlights human responsibility for climate change but can coincidentally leave the player with a sense of helplessness. Despite this feeling of futility, when games successfully convey human responsibility for climate change, they may yet help incite decisive action.15

The setting of a game jam can stimulate the creation of a game that challenges hegemonic structures. Earlier I mentioned Harrer’s notion of radical jamming, a form of game jam where the organisers use ideological constraints to encourage game design processes that challenges hegemonic structures. Harrer writes that radical game design is one of the ways in which organisers can operationalise their knowledge to challenge the default.16 The MGJ can be seen as a type of radical jamming: conventional game design practices are challenged with the introduction of new perspectives for climate justice, and reimagined climate futures.

Harrer describes three strategies that game jam organisers may apply to encourage radical game design. These strategies can also be recognised in the format of the MGJ. The first, radical theming, implies choosing a provocative theme to push design innovation. This strategy can be quickly identified in the MGJ’s primary theme of climate awareness. The second strategy is the use of technological constraints to support the inclusion of “…marginalised and novice video game developers.” While there was no specific technological constraint in the MGJ format, there were also no specific requirements for entering the jam as participant, other than active cooperation and attendance. This, in combination with a stipend, supported the potential inclusion of marginalised and novice game developers. The third strategy for radical jamming, self-expression, helps the participants share and learn more about themselves and others, which may “…stimulate intra- and interpersonal validation.”17 This strategy is reflected in the aims of the MGJ, and the content of the community talks provided during the game jam sessions.

There are many ways […] to contribute to a cause that you think is important, like for example climate justice. I think that’s what we wanted to do with the community talks: again inspire and just give like a different landscape of what games are, what can they do, and other ways of thinking of games.”

Karla Zavala Barreda.18

Jamming towards the future

The games developed during the Mzansi Game Jam can be accessed via the Mzansi Climate Justice Game Jam website. Each group in the jam was encouraged to create their own page on Itch.io, so they can share their games in the setting they so desire. This way, Barreda and Odendaal stimulate the participants to consider using game design in their future projects.

What at least we are trying to do is that – should the opportunity arise, let the participants and the games be the stars and tell them your stories. […] For us that is more interesting in this outreach part: so just to lay the ground of people sharing how interdisciplinarity can be, how games can be designed differently, or how to think differently about climate justice.”

Karla Zavala Barreda.19

In this article, game jams were analysed as a practical setting for game scholars and activists to share their insights, with the Mzansi Game Jam as case study. While there is a wide variety of game jams with only a broad definition to describe them, their setting can amplify the teaching of game design paradigms.20 In the case of the MGJ, hegemonic game design structures were actively challenged in pursuit of new perspectives on climate justice. In embracing a radical theme, technological constraints, and the self-expression of the participants, the MGJ can be seen as a type of radical jamming. The positive experiences of the participants and organisers, as well as their insights gained on the role game design can play in communicating an ecocritical message, show how the game jam can function as a platform to operationalise ideas originating from game studies and climate activism.

About the author:

Marijn Benschop is a New Media and Digital Culture Master student at Utrecht University. He wrote this article series as part of his internship at the Center for Game Research. He also co-organised Dutch DiGRA 2025.

- Harrer, Sabine. “Radical Jamming: Sketching Radical Design Principles for Game Creation Workshops” ICGJ proceedings 2019. pp. 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3316287.3316297 ↩︎

- Barreda, Karla Zavala, and Adriaan Odendaal. Interview by Marijn Benschop. October 2, 2025. Video, 01:35. ↩︎

- https://internetteapot.com/ ↩︎

- https://algorithmsoflatecapitalism.tumblr.com/workshop ↩︎

- https://climatejusticejam.net/updates/ ↩︎

- Barreda and Odendaal, interview. 06:05 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Idem, 03:18. ↩︎

- Kultima, Annakaisa. “Defining Game Jam.” FDG proceedings 2015. pp. 6. ↩︎

- https://globalgamejam.org/about, https://itch.io/jam/imaginary-game-jam-2024/results ↩︎

- Hrehovcsik, Micah, Harald Warmelink, and Marilla Valente. “The Game Jam as a Format for Formal Applied Game Design and Development Education.” In: Bottino, R., Jeuring, J., Veltkamp, R. (eds) Games and Learning Alliance. GALA 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 10056. Springer, Cham. pp. 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50182-6_23 ↩︎

- Kultima. “Defining Game Jam.” pp. 6. ↩︎

- https://climatejusticejam.net/ ↩︎

- Barreda and Odendaal. Interview. 18:19 ↩︎

- Makai, Peter Kristóf. “Do You Want to Set the World on Fire? Amplifying Player Agency to Demonstrate Alternatives to the Climate Crisis” In Ecogames: Playful Perspectives on the Climate Crisis. Eds. Op de Beke, Laura, Joost Raessens, Stefan Werning, and Gerald Farca. pp. 87, 90, 103-104. Amsterdam UP, 2024. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463721196 ↩︎

- Harrer. “Radical Jamming.” pp. 1-2. ↩︎

- Idem. pp. 2-3. ↩︎

- Barreda and Odendaal. Interview. 45:29 ↩︎

- Idem. 50:07 ↩︎

- Kultima. “Defining Game Jam.” pp. 2. ↩︎